… and other women who refused to live in silence and be consigned to oblivion*

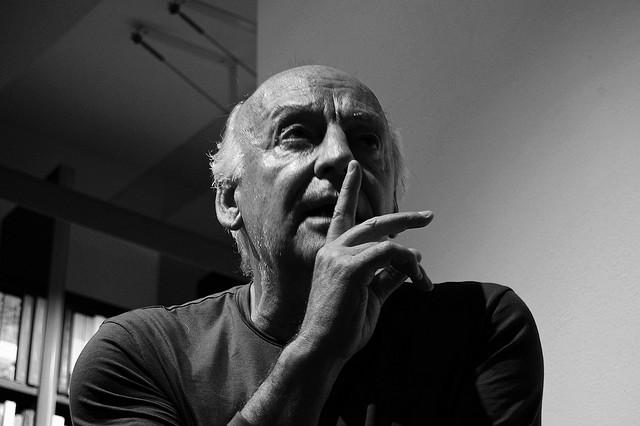

Por Eduardo Galeano**

The Shoe

(January 15)

In 1919 Rosa Luxemburg, the revolutionary, was murdered in Berlin.

Her killers bludgeoned her with rifle blows and tossed her into the waters of a canal.

Along the way, she lost a shoe.

Some hand picked it up, that shoe dropped in the mud.

Rosa longed for a world where justice would not be sacrificed in the name of freedom, nor freedom sacrificed in the name of justice.

Every day, some hand picks up that banner.

Dropped in the mud, like the shoe.

The Celebration That Was Not

(February 17)

The peons on the farms of Argentina’s Patagonia went out on strike against stunted wages and overgrown workdays, and the army took charge of restoring order.

Executions are grueling. On this night in 1922, soldiers exhausted from so much killing went to the bordello at the port of San Julián for their well-deserved reward.

But the five women who worked there closed the door in their faces and chased them away, screaming, “You murderers! Murderers, get out of here!”

Osvaldo Bayer recorded their names. They were Consuelo García, Ángela Fortunato, Amalia Rodríguez, María Juliache, and Maud Foster.

The whores. The virtuous.

Sacrilegious Women

(June 9)

In the year 1901, Elisa Sánchez and Marcela Gracia got married in the church of Saint George in the Galician city of A Coruña.

Elisa and Marcela had loved in secret. To make things proper, complete with ceremony, priest, license and photograph, they had to invent a husband. Elisa became Mario: she cut her hair, dressed in men’s clothing, and faked a deep voice.

When the story came out, newspapers all over Spain screamed to high heaven — “this disgusting scandal, this shameless immorality” — and made use of the lamentable occasion to sell papers hand over fist, while the Church, its trust deceived, denounced the sacrilege to the police.

And the chase began.

Elisa and Marcela fled to Portugal.

In Oporto they were caught and imprisoned.

The Right to Bravery

(August 13)

In 1816 the government in Buenos Aires bestowed the rank of lieutenant colonel on Juana Azurduy “in virtue of her manly efforts.”

She led the guerrillas who took Cerro Potosí from the Spaniards in the war of independence.

War was men’s business and women were not allowed to horn in, yet male officers could not help but admire “the virile courage of this woman.”

After many miles on horseback, when the war had already killed her husband and five of her six children, Juana also lost her life. She died in poverty, poor even among the poor, and was buried in a common grave.

Nearly two centuries later, the Argentine government, now led by a woman, promoted her to the rank of general, “in homage to her womanly bravery.”

Mexico’s Women Liberators

(September 17)

The centenary celebrations were over and all that glowing garbage was swept away.

And the revolution began.

History remembers the revolutionary leaders Zapata, Villa, and other he-men. The women, who lived in silence, went on to oblivion.

A few women warriors refused to be erased:

Juana Ramona, “la Tigresa,” who took several cities by assault;

Carmen Vélez, “la Generala,” who commanded three hundred men;

Ángela Jiménez, master dynamiter, who called herself Angel Jiménez;

Encarnación Mares, who cut her braids and reached the rank of second lieutenant hiding under the brim of her big sombrero, “so they won’t see my woman’s eyes”;

Amelia Robles, who had to become Amelio and who reached the rank of colonel;

Petra Ruiz, who became Pedro and did more shooting than anyone else to force open the gates of Mexico City;

Rosa Bobadilla, a woman who refused to be a man and in her own name fought more than a hundred battles;

and María Quinteras, who made a pact with the Devil and lost not a single battle. Men obeyed her orders. Among them, her husband.

The Mother of Female Journalists

(November 14)

On this morning in 1889, Nellie Bly set off.

Jules Verne did not believe that this pretty little woman could circle the globe by herself in less than eighty days.

But Nellie put her arms around the world in seventy-two, all the while publishing article after article about what she heard and observed.

This was not the young reporter’s first exploit, nor would it be the last.

To write about Mexico, she became so Mexican that the startled government of Mexico deported her.

To write about factories, she worked the assembly line.

To write about prisons, she got herself arrested for robbery.

To write about mental asylums, she feigned insanity so well that the doctors declared her certifiable. Then she went on to denounce the psychiatric treatments she endured, as reason enough for anyone to go crazy.

In Pittsburgh when Nellie was twenty, journalism was a man’s thing.

That was when she committed the insolence of publishing her first articles.

Thirty years later, she published her last, dodging bullets on the front lines of World War I.

But they escaped. They changed their names and took to the sea.

International Day for the Elimination of Violence Against Women

(November 25)

In the jungle of the Upper Paraná, the prettiest butterflies survive by exhibiting themselves. They display their black wings enlivened by red or yellow spots, and they flit from flower to flower without the least worry. After thousands upon thousands of years, their enemies have learned that these butterflies are poisonous. Spiders, wasps, lizards, flies, and bats admire them from a prudent distance.

On this day in 1960 three activists against the Trujillo dictatorship in the Dominican Republic were beaten and thrown off a cliff. They were the Mirabal sisters. They were the prettiest, and they were called Las Mariposas, “The Butterflies.”

In memory of them, in memory of their inedible beauty, today is International Day for the Elimination of Violence Against Women. In other words, for the elimination of violence by the little Trujillos that rule in so many homes.

In the city of Buenos Aires the trail of the fugitives went cold.

The Art of Living

(December 9)

In 1986 the Nobel Prize for medicine went to Rita Levi-Montalcini.

In troubled times, during the dictatorship of Mussolini, Rita had secretly studied nerve fibers in a makeshift lab hidden in her home.

Years later, after a great deal of work, this tenacious detective of the mysteries of life discovered the protein that multiplies human cells, which won her the Nobel.

She was about eighty by then and she said, “My body is getting wrinkled, but not my brain. When I can no longer think, all I’ll want is help to die with dignity.”

* This artcle originally appeared on TomDispatch. The passages are excerpted from Eduardo Galeano’s book Children of the Days: A Calendar of Human History, just out in paperback (Nation Books).

** Eduardo Galeano is one of Latin America’s most distinguished writers. He is the author of Open Veins of Latin America, the Memory of Fire Trilogy, Mirrors, and many other works. His newest book, Children of the Days: A Calendar of Human History (Nation Books), is just out in paperback and is excerpted in this piece. He is the recipient of many international prizes, including the first Lannan Prize for Cultural Freedom, the American Book Award, and the Casa de las Américas Prize.

Mark Fried is the translator of seven books by Eduardo Galeano including Children of the Days. He is also the translator, among other works, of Firefly by Severo Sarduy. He lives in Ottawa, Canada.